I read an article recently from Quartz titled "Is H&M misleading customer with all its talk of sustainability?" and it got me thinking about the sustainability of fast fashion (as a business model it's not, obviously, but I'll try to avoid confirmation bias). H&M is the world's largest fast fashion retailer, bringing in sales of $25 billion in FY 2015. Inditex (Zara) came in second at about $23.9 billion, and I reckon will surpass H&M soon given its growth rate; aptly named Fast Retailing (Uniqlo) netted $13.8 billion; and Gap Inc. (GAP, Old Navy), despite their constant steep discounts, managed to net $15.8 billion. Fast fashion is a monstrous industry holding immense influence over consumer buying power worldwide, and with the luxury market taking a slight dip in the ongoing recovery of the global economy among other issues, low prices never looked so attractive.

Average consumers are smarter and more informed by the day. We look for deals where we can find them and more often than not buying decisions are driven by price. So what are the trade-offs for throwaway prices?

- Cheaper fabric quality?

- Weaker construction?

- Fewer features and details, and therefore, product uniqueness?

- Immediate gratification?

- Our own psychological depreciation of product standards?

- Apathy for what we buy?

- Cheap labour, and therefore, social welfare?

- Integrity of ourselves and brands?

- Acceptance of "disposable" fashion?

Looking at the amount of money these companies bring in I question if we as consumers question the integrity of these companies and the way they do business, and H&M is the case study company. As a brand H&M regularly places among the top 100 globally in a variety of indices for brand recognition and value, and sustainability is no exception. Corporate Knights (CK), a Toronto-based consulting and research firm whose mandate focuses on "clean capitalism" and sustainability performance across a variety of fields, ranked H&M 20th in their 2016 Global 100 Most Sustainable Corporations (up from 75 in 2015). Superficially it looks good but what does this mean? How does one quantify sustainability meaningfully?

Measuring Sustainability

CK, which has been publishing the Global 100 since 2005, details the rating methodology (more detailed pdf) used consisting of four screens:

- Sustainability disclosure: Within this first screen, CK uses 12 key performance indicators (KPI) to measure a corporation’s compliance, of which at least nine (75%) must be reported. Each KPI is weighed equally and has an accompanying equation that quantifies a result thereby allowing comparison with peers. Measurables include productivity per unit of resource, employee compensation and safety, and diversity of leadership, among others.

- Piotroski F-Score: This test measures a company's financial strength, specifically in relation to its stock strength (i.e., to buy or short) and future performance. There are nine criterion to meet; one point is awarded for each satisfied criterion, with 0 being weak and 9 being strong. The Piotroski F-Score was developed by Joseph Piotroski, an accounting professor at Stanford University. His paper written in 2000 showed, using historical financial information, a 23% return from stocks bought and shorted through his method. For the purpose of the Global 100, CK requires a corporation to achieve a score of at least 5.

- Product category: The tobacco and defense (i.e., weapons manufacturing) industries are omitted, so by default H&M passes.

- Sanctions: Penalties, settlements, or fines paid related to sustainability infractions are considered as a percentage of revenue. CK runs a keyword search related to sustainability punitive payments for each company.

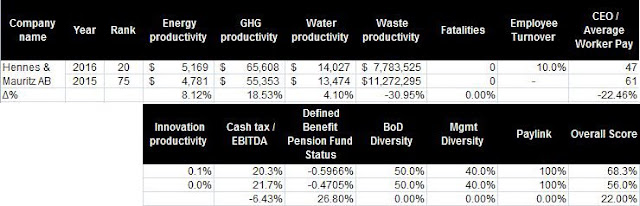

Above is H&M's 12 KPIs. The first four productivity indicators link directly with resource use, which is what most of us think when we think "sustainability." All four equations take revenue over a unit of resource, like one gigajoule of energy or cubic metre of water. The higher the numbers, the more revenue generated per unit of resource.

Waste productivity stands out as an anomaly. The resource unit is non-recyclable or unusable waste in metric tonnes. There's a 30% reduction in productivity from 2015 to 2016, meaning each metric tonne of waste produced resulted in almost one third less revenue in 2016. My guess is waste production increased rampantly relative to revenue considering it doesn't follow the upward trends of the other productivity factors, and sales increased by about 19%.

Another indicator to take note of is the ratio of CEO compensation relative to average worker pay. The CEO of H&M earned 61 times more than the average worker in 2015 and decreased to 47 in 2016. To put this in perspective, executive compensation back in the days of JP Morgan Jr. was 20 to one—a figure he proposed to be reasonable. Nowadays executive compensation can reach upwards of 500 times average employee pay depending on the industry (e.g., the CEO of Ecolab, ranked 50 on the Global 100, earned 594 to one); H&M's 47 is modest in that regard.

Board of Directors and Management diversity are other areas of interest. It's absurd that organisations still have problems with female representation at the executive level when numerous studies prove gender diversity affects positive growth and change. H&M scores well with Board of Directors representation at 50%—the highest of all CK Global 100 members—and is tied with several other companies in upper management diversity at 40% (44% being highest).

The second screen is satisfying the Piotroski F-Score and H&M barely squeaks by, tallying the minimum required 5, meaning moderate growth. The conditions where H&M scored were

- positive return on assets

- positive operating cash flow

- operating cash flow over assets is greater than return on assets

- no new issue of outstanding shares

- asset turnover is higher than previous year

Because the Global 100 has a quota for reserved spots proportionate to GICS sector representation in the MSCI ACWI it's not a list of the most sustainable, at least it doesn't appear that way. It's hard to compare numbers objectively by industry when H&M is the only fast fashion retailer listed.

Diversity should extend to ethnicity as well, not just gender. I take it most of these companies don't have very diverse ethnic representation and therefore renders any quantitative measurement meaningless.

The most apparent caveat of all, however, is the Global 100 doesn't account for social welfare of foreign suppliers, which is a big component of sustainability. Quantifying living standards for different countries based on H&M's impact is a daunting task in itself, and would have to be a whole new list entirely.

H&M's Sustainability Mission

H&M has a comprehensive sustainability manifesto, if you will, that takes the form of a long-form public relations infographic (beefy 130-page pdf available too) detailing trends and milestones. There are a few points I'm interested in.

CEO Interview: Written by the H&M PR team. His answers' contents are moderate and hopeful, and can be found in just about any statement released by large corporations preaching corporate social responsibility. In short, it sounds nice.

Fair living wage: Right off the bat H&M fails to convince any sort of real action. They hide behind the "complexity" argument, and I'm not saying it isn't complex, but because it is, H&M can't affect real change the way it claims it can. The first consideration is manufacturers work with many brands, not just H&M. If fair wages are to be negotiated and realised all brands and buyers must agree on what's fair together, which is something H&M emphasises several times in their sustainability report. Responsibility is spread out and ownership of the fair wage issue is diluted, which works in their favour.

H&M publishes a comprehensive list of its suppliers numbering in the thousands online. The majority of suppliers are concentrated in China (701), Bangladesh (300), India (233), and Turkey (305). With so many manufacturers, processing plants and fabric mills it's not practical nor realistic to track fair wage initiatives on even a fraction of them. Instead, H&M is focusing on implementing their fair wage initiative for all strategic suppliers (produce 100% H&M products) by 2018. For "priority" suppliers, it will be an on-going process which means H&M holds less influence over the social welfare of those suppliers and must rely on the good faith of competitors and local governments to affect change. This brings into question of how much influence can a foreign manufacturer have over government policy, as far as clothing manufacturers go. Would it make a difference if all or most fast fashion purveyors make an altruistic stand to government for increased social welfare of their countries? The fast fashion business model is low prices and producing large volumes with great speed. The ideas conflict.

Another consideration is scale, not just in terms of number of manufacturers, but number of brands working with them. The sustainability report mentions partnerships with the United Nations agency International Labour Organisation and IndustriALL Global Union to strengthen mediation with manufacturers. To IndustriALL's credit, its ACT programme, which focuses on the fabric and garment industry supply chains, has the cooperation of 17 brands which include H&M and its largest competitor Inditex. ACT works on the basis of industry collective bargaining, which means "... all workers and manufacturers in the garment sector within that country can negotiate their wages under the same conditions, regardless of which factory they work for, and which retailers and brands they produce for." It sounds pretty, it really does, and I don't mean to be cynical but how does one negotiate with 701 manufacturers in China and have all parties satisfied? Will it only work with smaller countries with fewer manufacturers?

The only way to establish truly improved living standards for overseas labour, especially in developing countries, even if they are experiencing economic growth, is for H&M to own and manage their own factories. That way they have full control over all operations (i.e., wages, working conditions, dare I say employee development) and determine what is fair or above average. Of course, this is unrealistic and simply won't happen. H&M relies on their suppliers to churn out thousands of tonnes of garments annually; it's the business model that brought in $25 billion last year. H&M is a low price, high volume competitor, and they're leading the way.

H&M Conscious: My take on the Conscious line, at least the men’s offering, is boring and basic. Nothing compels me to want to pick anything up and look at it. The only reason I would is to look at the manufacturing label for fabric content. Most of the Conscious garments have some percentage of recycled or organic fabric, depending on the nature of the garment, and sell for about the same price as their regular offerings. The "conscious" part of the campaign is the feel-good added value of knowing that part of the garment is made with sustainability in mind, but honestly, how many people read manufacturer's labels? From my experience, not very many. The green tag may be enough to convince someone that the $6 conscious tank top is better than the regular $6 offering. The problem comes full circle when we remember, once more, the business model of fast fashion: low prices, bulk volumes, speed of production and delivery of product.

In an ideal world, sustainability would mean locality:

- raw materials grown and processed locally and organically;

- process methods yielding high output per unit of resource use;

- labour is local so we know that even if it's minimum wage it's a standard all consumers can approve of;

- lower carbon footprint since transportation costs are reduced;

- all value-added steps within the supply chain would be at a higher cost than non-local production methods

H&M's Seven Commitments: This is where the manifesto takes shape. I think it's great H&M details their commitments, but they fall short in a few places.

- Choose and reward responsible partners: I find this commitment hard to wrap my head around from a supplier point of view. How can H&M source from thousands of suppliers and still says it's their choice who they work with? The fast fashion business model inherently conflicts with the idea of choice of source partners. H&M wouldn't be where it is today if it was selective about who it works with. It simply cannot push 600 million unit annually sourcing from responsible partners.

- Be ethical: Really...? I can't even.

- Reduce, Reuse, Recycle: The whole basis for H&M's sustainability and Conscious campaign, this commitment reinforces the ethos of fast fashion: that it's disposable. H&M, however, has made its stores into recycling centres for old garments and it will take all clothes regardless of brand or condition. This is a good marketing strategy because it creates a psychological response from the consumer to return to the store with their old clothes; they get the satisfaction of believing they're contributing to the company's sustainability initiatives and get discount incentives on their next purchase. We know this is purely business driven: one discount voucher per purchase over a stated minimum amount that H&M's quantitative experts determined would at least break even if not make a marginal profit in the store's overall sales.

- Strengthen Communities: Probably the most commendable commitment, strengthening communities conflicts with the fast fashion business model as well as H&M's responsibility to its shareholders. When the business model of making money depends on low cost production for low priced goods, it leaves little room for philanthropy other than to distract from the overall grim picture of overseas outsourced labour. Make no mistake, this commitment is also business driven. H&M's quantitative team, I'm sure, allocates an annual maximum expenditure limit of resources for community building activities like early child education programmes, and skills training and entrepreneurial development for women in sourcing countries. The goal is simply to divert people's attention while it strives to be the leader in fast fashion. Any commendation that comes out of the campaign is just value-added.

I applaud H&M for trying, even if it's a PR stunt. The reality is the marriage between sustainability and fast fashion cannot be fully realised as long as the business model remains unchanged, and if it did it would be something entirely different. To H&M's credit, its efforts have racked up a multitude of awards and stakeholder testimonials and furthers consumers' belief in the company's sustainability cause. In the end it’s all about how a brand controls customers’ perception of their corporate social responsibility efforts. But it is hard to overlook the many stories that tell otherwise.

Is it better than doing nothing? Yes. Will it convince customers the company is doing good? Yes. Are they misleading customers? Not if they're sceptical.

No comments:

Post a Comment